New study shows that perserverance can be the reason for antibiotic resistance development

Antibiotics were introduced in the 1930s and have since revolutionised modern medicine and healthcare. However, over the last few decades, antimicrobial resistance has started to pose a serious threat to global healthcare, animal husbandry, and the agricultural industry. Antimicrobial resistance means that bacteria and other microbes develop the ability to survive and grow in the presence of antibiotic drugs. In 2019, almost 1.3 million deaths were directly connected to antimicrobial resistance worldwide, and about 3 million resistant infections in the US alone. In Sweden, the corresponding number is about 10,000. Antimicrobial resistance is often referred to as a silent, or long-term pandemic. Decreased resistance development is central to future pandemic preparedness efforts, as we may enter an era where preventable disease can no longer be easily treated.

To study resistance development, it is possible to use either above-MIC (minimal inhibitory concentration) or sub-MIC concentrations of antibiotics. A bacterial population cannot grow at or above-MIC conditions; if no pre-existing mutations or resistance elements are present, all cells in the population will eventually die. In sub-MIC selection conditions, the bacteria can grow, albeit poorly, and cells that acquire de novo resistance mutations will have a selective advantage. Most studies of antibiotic resistance development are performed in batch cultures with large populations. This means that most studies overlook cell-to-cell heterogeneity in the response to antibiotic exposure. Additional studies into the heterogeneity in cellular responses to antibiotics and how these responses connect to antimicrobial resistance development are therefore warranted.

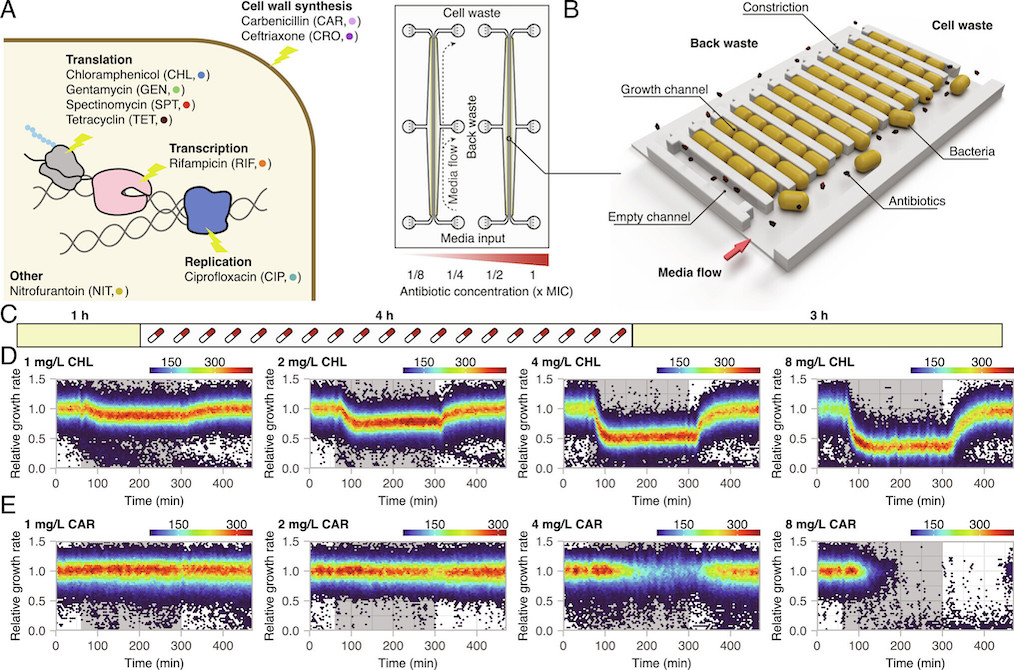

In a recently published article in PNAS, researchers from Science for Life Laboratory (SciLifeLab) and Uppsala University (First author: Gerrit Brandis; Corresponding authors: Gerrit Brandis, and Johan Elf) measured cell-to-cell heterogeneity in growth response as a function of antibiotic concentration, as well as how heterogeneity in antibiotic response affects antibiotic resistance development.

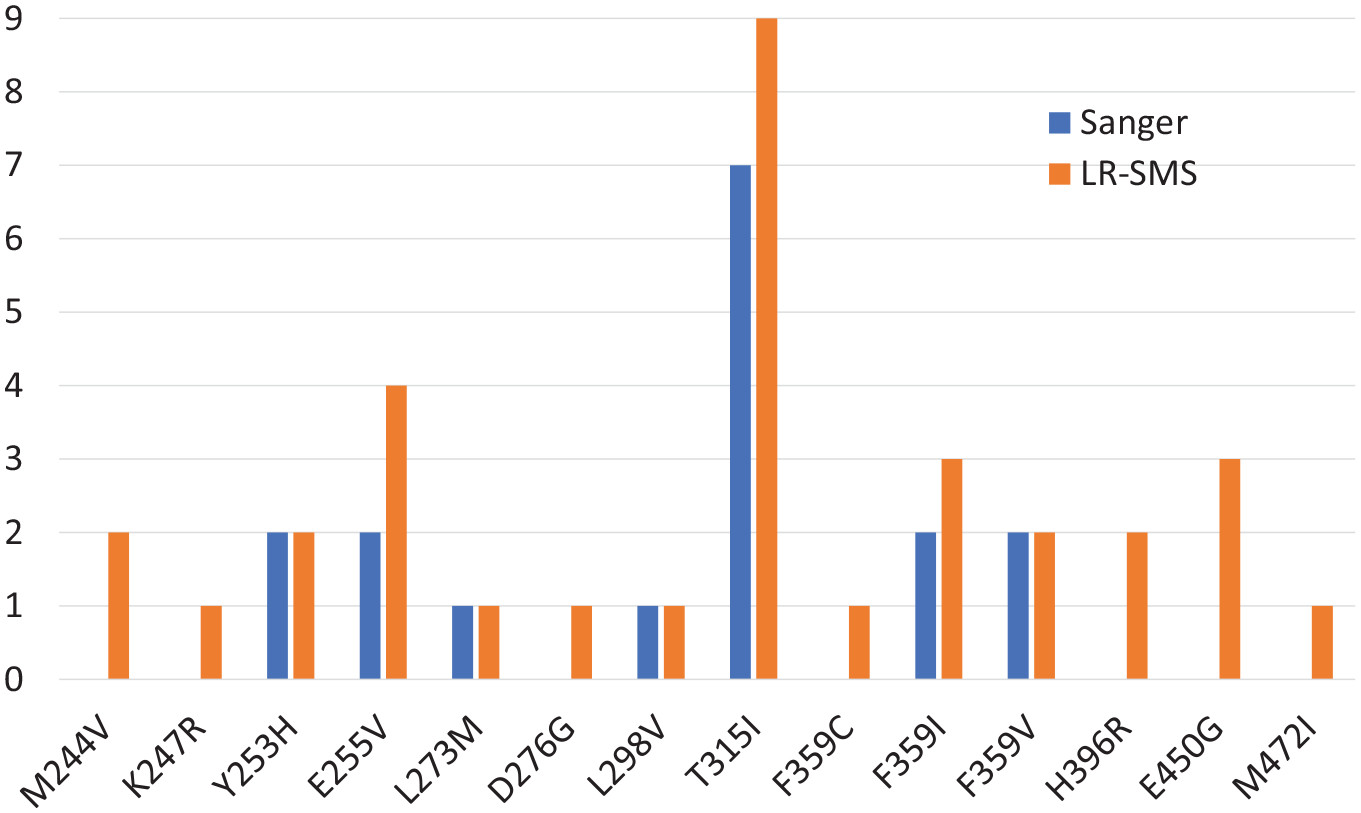

Brandis, Larsson, and Elf systematically exposed Escherichia coli to sub-MIC and above-MIC concentrations of nine antibiotics from a number of different antibiotic classes. They analysed the bacterial growth response on the single-cell level, using time-lapse microscopy. The results showed that the cell-to-cell heterogeneity, measured as the coefficient of variation of the growth rates of the cells, increased as a function of concentration and exposure time for all nine antibiotics studied. For three antibiotics (carbenicillin, ceftriaxone, and gentamycin), the difference in growth increased more than what was expected from simple growth rate reduction. In addition, in the presence of rifampicin and nitrofurantoin, sub-populations of bacteria continued to grow at above-MIC antibiotic concentrations for up to 10 generations. The researchers defined antibiotic perseverance as the ability of a subpopulation to maintain replication longer than the main population even at the MIC. They also found that the presence of antibiotic perseverance increased the risk of antibiotic resistance development by up to 40-fold in gram-negative and gram-positive species.

Previous research has indicated that heteroresistance, a phenomenon where parts of the population can sustain growth above MIC, and persistence (the ability to tolerate higher dosages of antibiotics by entering a dormant state) are factors that contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance. However, the bacteria identified in this study are not resistant; their ability to grow in the presence of the drug is likely due to chance. But with each cell division, there’s a risk that a resistance mutation might occur. This is one of the rationales behind the recommendation to adhere strictly to antibiotic prescriptions and not terminate the treatment prematurely.

“This is a new concept that we call antibiotic perseverance,” explains Gerrit Brandis, a researcher in the group. “Perseverance describes how a small group of bacteria capable of sustaining growth can accumulate mutations after being exposed to antibiotics. If they are lucky, and the patient unlucky, one of these mutations will allow them to tolerate the antibiotic.”

In summary, studies of bacteria on the single-cell level have revealed new information about a small sub-population of bacteria that survives in the presence of antibiotic concentrations that would normally kill them. Brandis, Larsson and Elf concluded that so called antibiotic perseverance is a common phenomenon and that it may also potentially have effect on the development of antibiotic resistance across pathogenic bacteria.

Data

- Raw microscopy image data and computational code used for analysis and plotting have been deposited here.

- Supporting information is also available in the full text version of the article

Article

Brandis, G., Larsson, J., & Elf, J. (2023). Antibiotic perseverance increases the risk of resistance development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120 e2216216120. 10.1073/pnas.2216216120.

Funding

The study was funded by the European Council, The Swedish foundation for Strategic research, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and the eSSENCE initiative.

Learn more about the Elf group here: https://elflab.icm.uu.se