New DNA research into Bantu-speaking populations' expansion provides a resource for future studies

In a recent Nature article, researchers from Uppsala University, SciLifeLab, and Stockholm University, along with international research collaborators from Europe and Africa (First authors: Cesar A. Fortes-Lima, Concetta Burgarella, Rickard Hammarén; Corresponding author: Carina M. Schlebusch) used genetic analysis of modern and ancient individuals to study the expansion of people speaking Bantu languages (BSP).

Today, 350 million people across Africa (about 30% of the total population) speak one or more of the around 500 Bantu languages. The expansion of people speaking Bantu languages is considered one of the most dramatic demographic events in Late Holocene Africa. The Holocene is the current geological epoch, from ~12000 years ago until the present day.

Previous studies in linguistics, archaeology, and genetics have, to date, not found the typical serial-founder effect (when small migrant groups settle in new areas, genetic diversity decreases with increasing distance from their origin) for the Bantu expansion. Newer population genetic methods and modeling approaches, which are spatiotemporally sensitive, are therefore warranted.

Archeological findings, such as specimens, clay artifacts, jewelry, and other remnants, were traditionally the only way to study ancient cultures, and how humans expanded in a region. In recent decades, ancient DNA (aDNA) has expanded and enhanced our knowledge of human history. Today, DNA research is an important tool in both the natural (e.g. medicine and health) and social sciences (e.g. archeology and linguistics).

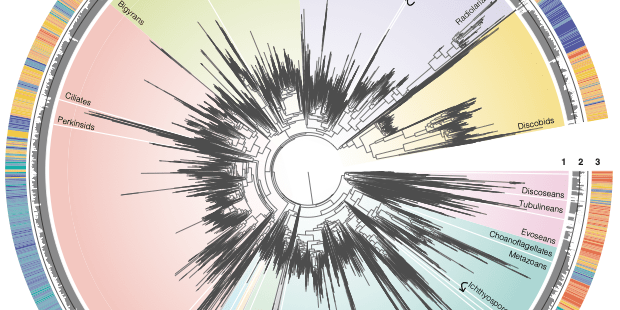

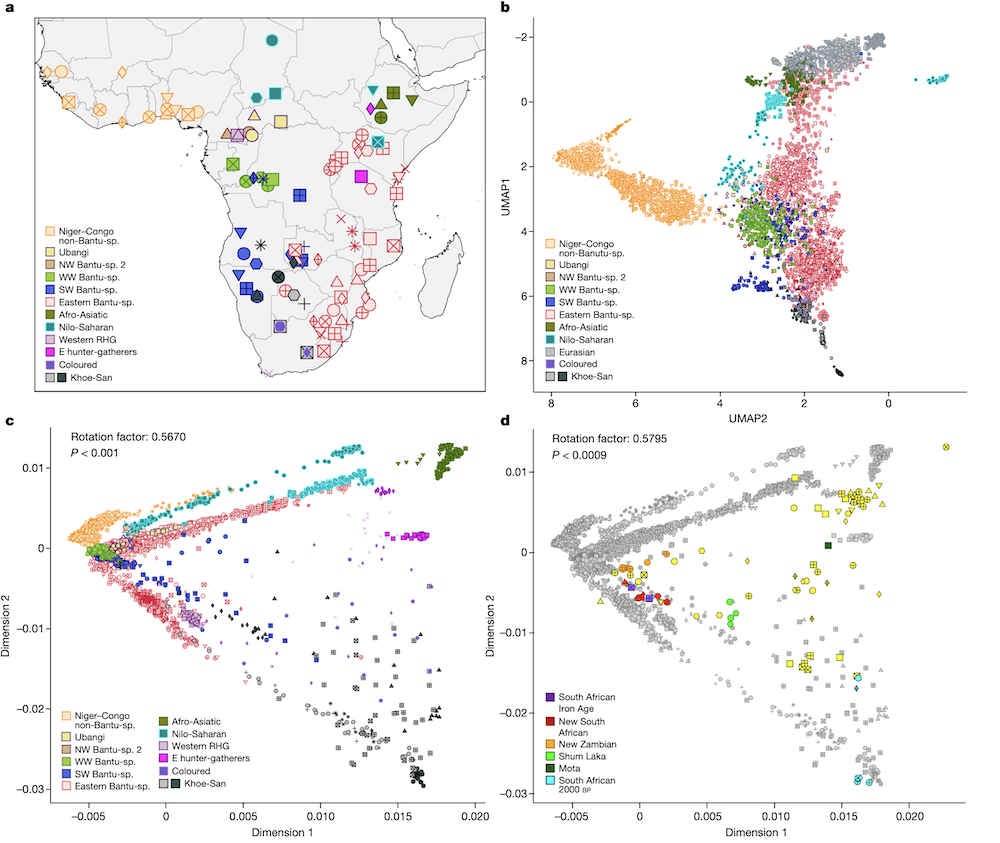

Today, whole-genome studies (WGS) of African populations are available, but comprehensive genomic data for BSP from sub-Saharan Africa remain limited. Fortes-Lima, Burgarella, and Hammarén and colleagues, therefore, collected and genotyped a new dataset called the “African Neo” dataset. This dataset consists of 1,526 Bantu speakers from 147 populations across 14 African countries, as well as aDNA WGS data from 12 Late Iron Age individuals found in Zambia. This comprehensive “African Neo” dataset was used to study the demographic history of BSP using various methods such as allele-frequency and haplotype-based methods, genetic diversity summary statistics, and spatial modeling.

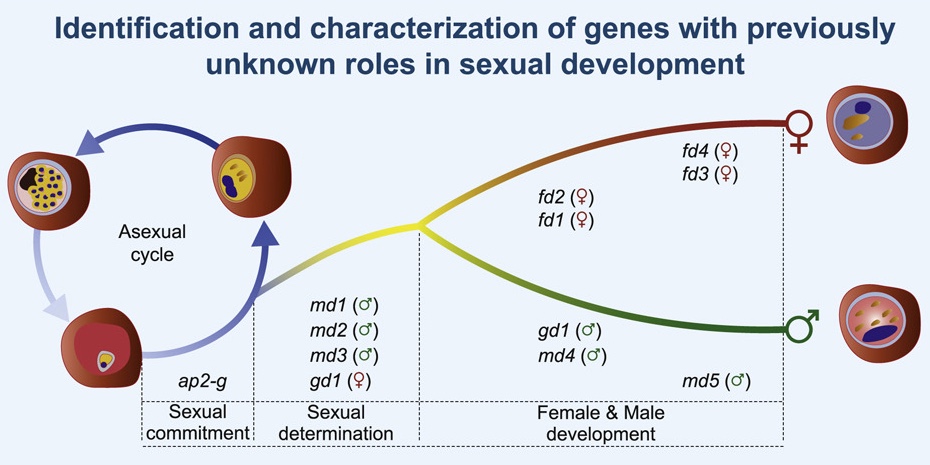

In brief, the results revealed different patterns of admixture between studied and local groups in different regions of sub-equatorial Africa where BSP expanded. The significant gene flow from local groups residing in the regions where the Bantu speakers expanded into suggests that Bantu speakers assimilated into local groups. Overall, the findings suggest that the BSPs expanded out of West Africa and moved south and east in several waves.

Furthermore, the possibility of so-called “spread-over-spread” events was evaluated by comparing the genetic diversity of present-day BSP with DNA from ancient individuals (aDNA). The aDNA WGS data of 12 individuals from Zambia and South Africa was complemented by additional WGS data from 83 individuals from different parts of Africa from previous aDNA studies.

The results showed that Late Iron Age aDNA individuals found in South Africa showed homogeneity and genetic affinity with local, modern BSP, which points to genetic continuity since the Late Iron Age. However, the Late Iron Age aDNA individuals from Zambia showed a more heterogeneous genetic makeup in and showed genetic affinities with modern BSP from a larger geographical area.

In summary, Fortes-Lima, Burgarella, Hammarén, and colleagues show that the genetic history of Bantu-speaking people is complex and suggests a serial-founder migration model. These results show that genetic diversity amongst BSPs declined with distance from western Africa, with current-day Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo as possible crossroads of interaction. This challenges previous models of the expansion of Bantu-speaking populations based on single disciplinary studies. In addition, the researchers propose the use of the new genetic dataset “AfricanNeo” as an important resource for a wide range of disciplines including medicine, health, science, and humanities. The dataset could, for example, be used to study human genetic variation and human health in African and African-descendant populations.

Article

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06770-6

Fortes-Lima, C.A., Burgarella, C., Hammarén, R. et al. (2023). The genetic legacy of the expansion of Bantu-speaking peoples in Africa. In: Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06770-6.

Funders

This project was funded by a large number of national and international funders e.g. ERC Horizon 2020, Swedish Research Council, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Swedish Research Council, Wellcome Trust, Horizon 2020, the Marcus Borgströms Foundation, the Sven and Lilly Lawski Foundation, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, and the European Regional Development Fund.

Data availability

- NP array genotype data of modern-day African populations and WGS of aDNA individuals generated in this project were made available through the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA) data repository (EGA accessory numbers: EGAS50000000006 and EGAS00001007519 for modern and aDNA, respectively).

- Controlled-access policies guided by participant consent agreements will be implemented by the African Neo Data Access Committee (AfricanNeo DAC accessory: EGAC00001003398).

Copies of the plots, and interactive versions of the plots, are available on GitHub and FigShare. The code used to generate the plots is available on GitHub.

Infrastructure

The genotyping and sequencing were performed by the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform, NGI/SciLifeLab Genomics. Computations/data handling were enabled by resources provided by the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS) at UPPMAX.