New study shows crossing the salt barrier has shaped the diversity of life

Successfully colonising a new habitat is a key evolutionary event. Over the course of animal and plant diversification, transitions between marine and non-marine habitats have seldom occurred. This habitat boundary, called the “salt-barrier”, is one of the hardest barriers to cross due to the strong shift in salinity and osmotic pressure. However, most eukaryotic diversity is in fact microbial (with larger population sizes and dispersal capabilities) and there is debate on how frequently these microbes have achieved marine/non-marine cross colonisations. The role of the salt barrier in shaping eukaryotic diversity at a broad scale is thus unknown.

A recent study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution has now used a combination of long-read and short-read metabarcoding data to investigate how habitat preference has evolved across the eukaryotic tree of life. The work involved Uppsala University researchers along with a team of international collaborators (First author: Mahwash Jamy, Uppsala University; Corresponding author: Fabien Burki, Uppsala University/SciLifeLab).

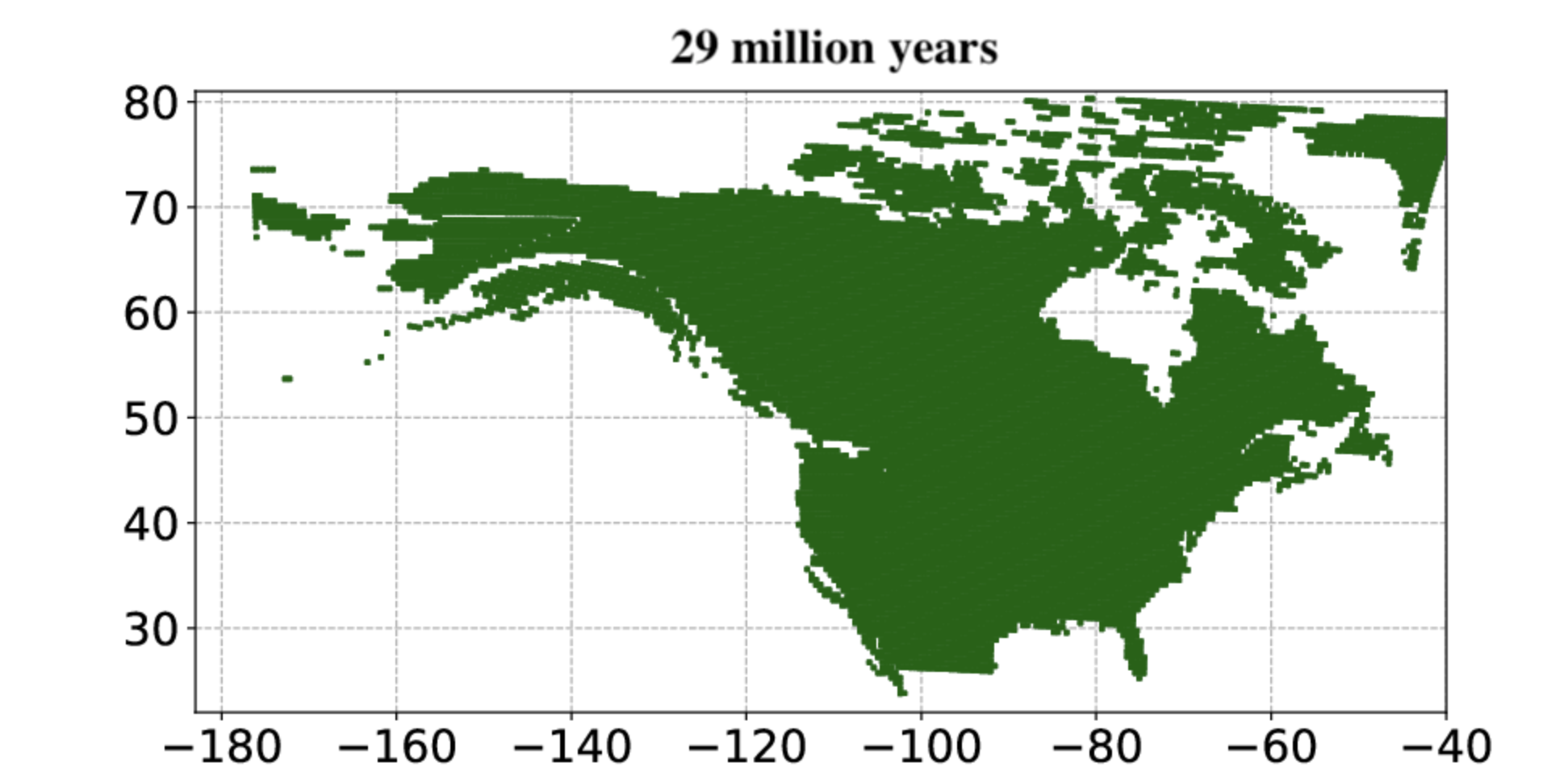

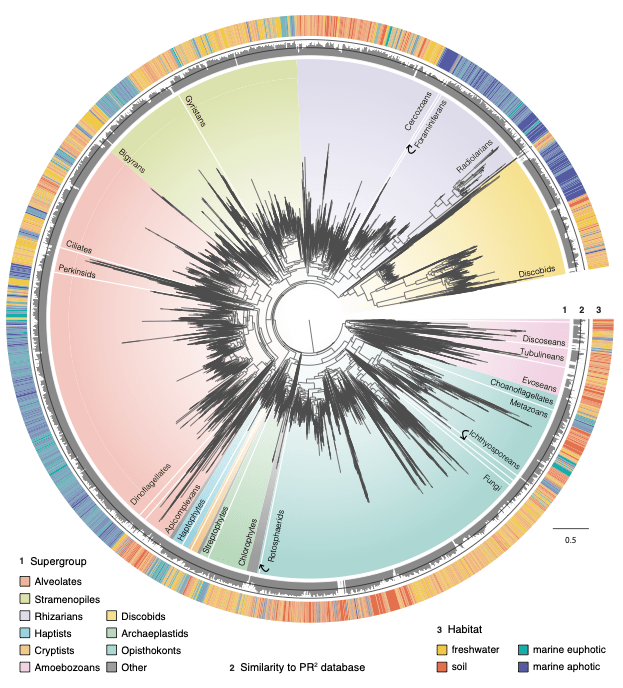

Jamy and colleagues first generated nearly 10 million long environmental reads (~4,500 bp spanning the ribosomal DNA operon) from 21 samples including Swedish freshwater lakes, permafrost thaw ponds, boreal and tropical forest soils, and oceans waters from the surface to the depths of the Mariana Trench. The long reads have increased phylogenetic signal, which (after clustering into ~17,000 taxonomically labeled OTUs) could be used to calculate phylogenetic trees spanning all major eukaryotic groups. Taxon sampling was further increased by incorporating publicly available short-read metabarcoding data (~234 million reads) from >1,500 samples globally (this dataset is available in a recently published article; see Vaulot et al. (2022) and metaPR2 database).

These large, comprehensive phylogenies were used to model habitat preference evolution across two billion years of eukaryotic evolution. Results showed that marine and non-marine organisms are phylogenetically distinct in general, indicating that the salt-barrier is difficult to cross even for microbes. However, microbial eukaryotes have achieved colonisations across marine/non-marine ecosystems several hundred times during their diversification. These were key events that likely allowed them to colonise vacant ecological niches. Moreover, the results showed that several clades were more adept at transitioning to new habitats, including diatoms, golden algae, and especially fungi. Finally, the researchers could infer the ancestral habitats inhabited by early eukaryotes, and found that the two largest groups, Amorphea and TSAR, likely arose in different habitats. The TSAR lineage (which contains diatoms, ciliates, dinoflagellates, radiolarians etc.) likely arose in the Precambrian oceans, while the ancestral Amorphean (which has now diversified into fungi, animals, choanoflagellates, and amoebozoans) likely inhabited non-marine habitats.

In summary, Jamy and colleagues examined how habitat preference has evolved across the global tree of eukaryotes. Their results show that crossings across the salt-barrier have likely been key evolutionary events, resulting in the vast eukaryotic diversity we see today.

Data

-

All Raw PacBio long-read sequence data is available in the European Nucleotide Archive PRJEB45931 and PRJEB25197

-

Publicly available short-read data are available from the metaPR2 database.

-

Taxonomically annotated long-read OTUs (18S and 28S), clustered short-read sequences, and all phylogenetic trees are available on FigShare

-

All code for analyses has been deposited at Zenodo

Article

Jamy, M., Biwer, C., Vaulot, D., Obiol, A., Jing, H., Peura, S., Massana, R., & Burki, F. (2022). Global patterns and rates of habitat transitions across the eukaryotic tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 6(10), 1458-1470. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01838-4

Funding

This research was funded by SciLifeLab, and the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Competitiveness projects Malaspina-2010 (CSD2008–00077) and ALLFLAGS (CTM2016-75083-R). Work performed at NGI/Uppsala Genome Center has been funded by RFI/VR and SciLifeLab. The Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing (SNIC) at UPPMAX, which is partially funded by the Swedish Research Council, was used for some parts of the study.